Over the past decade, software architecture in pharma and biotech has evolved from tightly coupled monoliths to modular, distributed systems built on microservices.

While some have dismissed this as a technical trend, the shift reflects a deeper transformation—one that impacts how teams collaborate, innovate and scale within complex, regulated environments.

Architecture is no longer just a technical decision. It is an operational one, a regulatory one, and above all, a strategic one.

Just as the move from DevOps to platform engineering changed how teams think about ownership and delivery, the journey from monoliths to microservices redefines how we think about systems, scale and scientific software.

Recognizing the limits of the monolith

For many pharma and biotech organizations, the story starts with a monolith: a single application responsible for everything from clinical trial data entry to regulatory submissions.

These systems were often efficient at first—fast to build, easy to host, and tightly aligned with a single use case.

But as organizations grew and added more functions, including real world data integration and AI model deployments, cracks started to show. A single failure could bring the entire platform down. Scaling one feature meant scaling everything. Teams were blocked, waiting on centralized updates. Releases took weeks owing to tight coupling and shared databases.

What began as a unified system slowly turned into a bottleneck for scientific innovation.

The tipping point: scientific scale and regulatory complexity

The tipping point came when R&D teams began demanding more autonomy. Bioinformatics groups wanted to deploy machine learning models into production. Clinical teams needed to integrate third-party data vendors. Regulatory affairs needed traceability and version control at every step.

The monolith could not keep up.

Each team had unique needs, but all were bound to the same release cycle. Every request to the central engineering team was met with delays, risk assessments and prioritization debates. Over time, it became clear that this was not just an architecture problem—it was an organizational alignment problem.

Reimagining architecture as an enabler

The transition to microservices began with a mindset shift: architecture should enable science, not constrain it.

Early on, small, low-risk services were carved out of the monolith: a metadata catalog for compound screening, a separate ingestion pipeline for real-world evidence, and a standalone model-serving endpoint for AI-powered biomarker discovery.

These were not just technical experiments; they were trust-building exercises. Each successful microservice gave a team more control, improved performance and reduced the load on centralized infrastructure.

The architecture was no longer a rigid stack. It was becoming a platform—one built on composability, autonomy and accountability.

Lessons learned in the transition

- 1. You can not rewrite the monolith overnight

- In regulated environments, rewriting core systems is not always feasible. Instead of replacing the monolith, we surrounded it. New services were built on cloud-native stacks and slowly replaced monolithic dependencies. The monolith itself was refactored into smaller, deployable components over time.

- 2. Not everything needs to be a microservice

- Some tools, like internal dashboards or ELN integrations, remained monolithic by design. We learned to focus microservice efforts where they added the most value for high-scale, high-change and high-risk areas.

- 3. Security and compliance must be first class citizens:

- Microservices added flexibility but also complexity. Every service needed proper authentication, auditability and documentation. A security-by-default approach became a non-negotiable requirement, not an afterthought.

- 4. Organizational structure follows architecture:

- As services grew, so did the teams around them. Bioinformatics, clinical ops, regulatory, and data science teams each began owning parts of the platform. The shift was no longer just technical, but it was cultural.

Microservices and MLOps: unlocking scientific acceleration:

Nowhere was the architecture shift more impactful than in R&D.

In the monolith era, a data scientist might train a model and email the output to engineering for integration.

With microservices and proper MLOps, the workflow changed completely:

- Feature engineering pipelines became reusable services.

- Models were deployed via versioned APIs with A/B testing.

- Training and inference were decoupled and scalable.

- Model metadata was tracked in a centralized registry.

- Scientists could deploy updates without waiting weeks for release windows.

- This did not just make model deployment faster. It made experimentation reproducible, regulatory audits cleaner, and collaboration easier across multidisciplinary teams.

Measuring progress and building for the future:

Just like in platform engineering, we tracked our progress with metrics: service uptime, release frequency, incident response time, model reusability. Every data point told a story of increasing agility, better quality and reduced bottlenecks.

We did not abandon monoliths entirely. They still serve key purposes. But we now treat them as part of a larger architecture, not the whole system.

By adopting microservices where it made sense, we built a more flexible, secure and scalable foundation for scientific innovation.

What is next: OrgOps for scientific systems

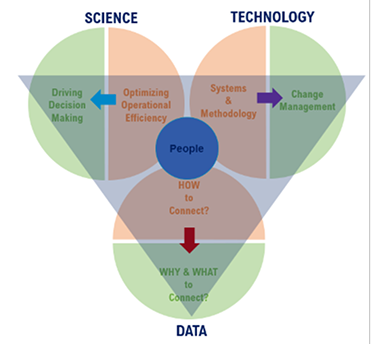

As more teams adopt microservices, the conversation is evolving again toward something like OrgOps. This means architecture, process, and policy are all integrated across the organization. It is no longer just about developers or data scientists. It includes quality, regulatory, compliance, and IT security as active contributors to the system lifecycle.

In this new world, the architecture becomes a living organism—a reflection of how the company thinks about experimentation, risk, and growth.

The transition from monolith to microservices is not a one-time migration. It is an ongoing journey. For pharma and biotech organizations, it is a path toward greater agility, transparency and innovation.

Architecture, when done right, becomes more than a framework. It becomes a force multiplier—accelerating drug discovery, enabling compliance and empowering the people who make science happen.