1. Abstract

Advancements in whole-genome sequencing (WGS) technologies have revolutionized the study of pathogenic microbes, offering detailed insights into their genetic composition and transmission patterns. This study explores the use of Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) for WGS-based single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) typing of Francisella tularensis subsp. Holarctica, Brucells suis, and Bacillus anthracis. We compare data from ONT R9 and R10 flow cells with Illumina short-read sequencing to evaluate performance across multiple metrics, including read quality, assembly contiguity, SNP detection, and phylogenetic clustering. Our findings highlight both the benefits of ONT—such as long-read capacity for resolving repetitive regions—and its current limitations, including challenges in homopolymer resolution and species-specific DNA modifications. We also discuss workflow adjustments and emerging tools that may further improve ONT accuracy in microbial genomic analysis. This work provides practical guidelines for researchers considering ONT for pathogen genome characterization and underscores the need for application-specific approaches when selecting sequencing technologies.

2. Introduction

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has become a cornerstone in understanding microbial pathogens, enabling precise identification of genetic variants and the reconstruction of outbreak dynamics. Short-read sequencing technologies, such as Illumina, have traditionally dominated this space owing to their high accuracy and cost-effectiveness. However, limitations in resolving repetitive regions and larger structural variants have prompted researchers to explore alternative platforms, including Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT). ONT’s portable devices offer long-read sequencing capabilities and have gained increasing attention for field-based and point-of-care applications.

Despite the promise of ONT, its performance can vary significantly across different microbial species and experimental conditions. To address these concerns, we conducted a comparativestudy of ONT (R9.4.1 and R10.4 flow cells) and Illumina sequencing platforms for the whole-genome analysis of three pathogenic bacteria: Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica, Brucella suis, and Bacillus anthracis. We specifically focused on SNP typing and phylogenetic inference to assess the impact of technology choice on downstream analyses.

In the sections that follow, we review the current literature on ONT’s application to microbial genomics (Section 3) and discuss the latest updates in ONT flow cells and basecalling (Section 4). We then highlight the advantages and limitations of ONT for de novo assembly and variant detection (Section 5). Subsequently, we present our dataset, analysis workflow, and results (Sections 6–8), including assembly metrics, SNP calls, and phylogenetic trees. Finally, we discuss the challenges and limitations observed in this study (Section 9) and suggest avenues for further research.

3. Oxford Nanopore sequencing technology and microbial analysis

Having established the motivation for exploring ONT in pathogen genomics, we now turn to a review of Oxford Nanopore sequencing technology and its applications in microbial analysis.

Various studies have investigated Oxford Nanopore sequencing technology for its potential applications in microbial analysis. Research has explored its capacity to address particular challenges associated with short-read sequencing methods. Studies have examined the long-read capability of the technology, particularly in resolving repetitive regions and structural variants (Amarasinghe et al., 2020). Investigations into GC bias patterns in Nanopore sequencing have been conducted, comparing them with those observed in some short-read platforms (Laver et al., 2015). Additionally, the potential of Nanopore sequencing for generating contiguous microbial genome assemblies has been a focus of research (Wick et al., 2017). While some researchers have considered Oxford Nanopore as an option for microbial genomic analysis, its efficacy depends on specific applications and experimental conditions (Tyler et al., 2018). Further research may be required to fully understand the strengths and limitations of this technology across different microbial analysis contexts.

4. ONT - Current trends and updates

While the long-read capabilities of ONT have addressed some limitations of short-read sequencing, recent updates in ONT hardware and basecalling software continue to shape its performance. The next section highlights current technological advancements and trends.

Recent developments in ONT over the past years have shown advancements in library preparation methods and the transition from R9 to R10 series flow cells. The R9 series, particularly the R9.4.1 flow cells, have been widely used in various applications, while the newer R10 series, including R10.3 and R10.4, have been introduced to improve sequencing accuracy (Nurk et al., 2022). Research suggests that the R10.4 flow cell, with its improved sequencing accuracy and reduced error rates, may offer enhanced performance in homopolymer resolution compared to R9.4.1. However, comparative analyses suggest that each type may have specific strengths depending on the application (Sereika et al., 2022). For basecalling, which converts raw electrical signals to nucleotide sequences, efforts to improve accuracy and speed through updated algorithms and software have been ongoing, with regular updates to tools like Guppy and Bonito (Wick et al., 2022). ONT has also introduced a Nanopore-Only Microbial Isolate Sequencing Solution, described as an end-to-end workflow for microbial genome sequencing (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, 2023). This development potentially offers a streamlined approach for the infectious disease research community, though its efficacy across various research contexts remains a subject of ongoing investigation.

5. Advantages of ONT

Building on these recent developments in ONT library preparation and basecalling, we now outline the key advantages that ONT offers for microbial genome assembly and variant detection.

Studies investigating ONT's utility in de novo genome assembly have reported the relative ease of assembly processes compared to short-read technologies (Tange et al., 2021). A variety of genome assembly tools optimized for ONT data have been developed and evaluated, including software such as Flye and Canu, each with reported strengths and limitations (Kolmogorov et al., 2019; Koren et al., 2017). Further, exploration of the capacity of ONT long reads to span repetitive regions has revealed potential benefits in resolving complex genomic structures (Charalampous et al., 2019). Additionally, research into ONT's ability to detect structural variations suggests improved sensitivity for certain types of variants (Sedlazeck et al., 2018). The portability of ONT devices has also been noted in several studies, with researchers examining their potential for field-based or point-of-care applications (Jain et al., 2016). However, comparisons of genome assembly quality between ONT and other sequencing platforms have produced varied results, largely depending on the organisms and methodologies used (Wick et al., 2019). Therefore, it is important to note that the performance and advantages of ONT technology can vary depending on the specific application, experimental design, and analytical approach. For example, data generated using R10.4 sequencing enzyme with the latest Q20+ chemistry, compared to data generated with R9.4.1 chemistry, improved ONT’s SNV detection capabilities and yielded comparable results for SV and overall methylation detection (Ni et al., 2023).

6. Datasets

Having discussed the overall advantages and potential utility of ONT for microbial genomics, we next describe the datasets and workflows used in our comparative study.

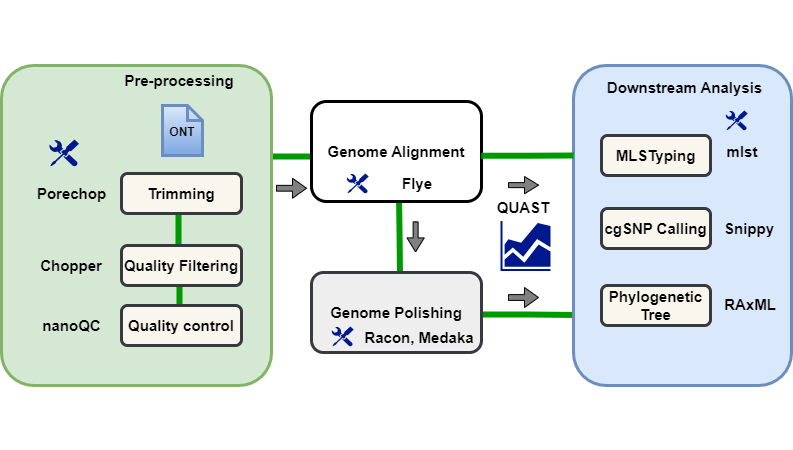

The data used for the analysis were publicly available from BioProject (ID: PRJEB59317). The analysis workflow (Figure 1) performed was adapted from an already published study with certain modifications to meet the objectives (Linde et al., 2017). For short reads, we followed a standard workflow using short-read–specific tools until the assembly step of the workflow. After the assembly step, we used the same tools for downstream analysis of both short reads and long ONT reads. The ONT dataset was readily available as FASTQ files. We took a subset of samples and proceeded with our analysis. The raw ONT files were converted to FASTQ files using Guppy (v6.0.1) basecaller utilizing the dna_r9.4.1_450bps_sup model for R9ONT and dna_r10.4_e8.1_sup.Cfg model for R10ONT. The same basecaller tool was also used for demultiplexing and trimming of the barcodes.

Table 1: Sample information for input data. The selected species include Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica (yellow), Brucella suis (blue), and Bacillus anthracis (green). Nine samples from each species were analyzed using various sequencing technologies, including Illumina, R9ONT, and R10ONT amounting to a total of 27 samples.

| Run IDs | BioSample | Strain IDs | Genomic Size (MB) | Spots | Library Layout | Technology | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERR10820717 | SAMEA112370825 | 08T0013 | 234 | 1056616 | PAIRED | ILLUMINA | Francisella tularensis |

| ERR10828745 | SAMEA112370825 | 08T0013 | 265 | 16654 | SINGLE | ONT - R9 | Francisella tularensis |

| ERR10828751 | SAMEA112370825 | 08T0013 | 280 | 26447 | SINGLE | ONT - R10 | Francisella tularensis |

| ERR10820719 | SAMEA112370827 | 10T0192 | 211 | 940770 | PAIRED | ILLUMINA | Francisella tularensis |

| ERR10828747 | SAMEA112370827 | 10T0192 | 359 | 27010 | SINGLE | ONT - R9 | Francisella tularensis |

| ERR10828753 | SAMEA112370827 | 10T0192 | 274 | 29877 | SINGLE | ONT - R10 | Francisella tularensis |

| ERR10820721 | SAMEA112370829 | 15T0012 | 172 | 726495 | PAIRED | ILLUMINA | Francisella tularensis |

| ERR10828749 | SAMEA112370829 | 15T0012 | 648 | 49200 | SINGLE | ONT - R9 | Francisella tularensis |

| ERR10828755 | SAMEA112370829 | 15T0012 | 173 | 24958 | SINGLE | ONT - R10 | Francisella tularensis |

| ERR10820711 | SAMEA112370831 | 08RB2802 | 253 | 692799 | PAIRED | ILLUMINA | Brucella suis |

| ERR10828733 | SAMEA112370831 | 08RB2802 | 325 | 61974 | SINGLE | ONT - R9 | Brucella suis |

| ERR10828739 | SAMEA112370831 | 08RB2802 | 110 | 24041 | SINGLE | ONT - R10 | Brucella suis |

| ERR10820714 | SAMEA112370834 | 08RB3701 | 265 | 817936 | PAIRED | ILLUMINA | Brucella suis |

| ERR10828736 | SAMEA112370834 | 08RB3701 | 297 | 58803 | SINGLE | ONT - R9 | Brucella suis |

| ERR10828742 | SAMEA112370834 | 08RB3701 | 108 | 24712 | SINGLE | ONT - R10 | Brucella suis |

| ERR10820716 | SAMEA112370836 | 15RB2242 | 258 | 796321 | PAIRED | ILLUMINA | Brucella suis |

| ERR10828738 | SAMEA112370836 | 15RB2242 | 307 | 57178 | SINGLE | ONT - R9 | Brucella suis |

| ERR10828744 | SAMEA112370836 | 15RB2242 | 140 | 30436 | SINGLE | ONT - R10 | Brucella suis |

| ERR10820686 | SAMEA112370837 | 12RA1944 | 353 | 1304222 | PAIRED | ILLUMINA | Bacillus anthracis |

| ERR10828757 | SAMEA112370837 | 12RA1944 | 997 | 123183 | SINGLE | ONT - R9 | Bacillus anthracis |

| ERR10828763 | SAMEA112370837 | 12RA1944 | 229 | 33303 | SINGLE | ONT - R10 | Bacillus anthracis |

| ERR10820687 | SAMEA112370838 | 12RA1945 | 336 | 1281935 | PAIRED | ILLUMINA | Bacillus anthracis |

| ERR10828758 | SAMEA112370838 | 12RA1945 | 2074 | 230225 | SINGLE | ONT - R9 | Bacillus anthracis |

| ERR10828764 | SAMEA112370838 | 12RA1945 | 609 | 79516 | SINGLE | ONT - R10 | Bacillus anthracis |

| ERR10820690 | SAMEA112370841 | 14RA5915 | 338 | 1326955 | PAIRED | ILLUMINA | Bacillus anthracis |

| ERR10828761 | SAMEA112370841 | 14RA5915 | 1752 | 206807 | SINGLE | ONT - R9 | Bacillus anthracis |

| ERR10828767 | SAMEA112370841 | 14RA5915 | 310 | 43146 | SINGLE | ONT - R10 | Bacillus anthracis |

Figure 1: Analysis workflow comparing ONT R9 vs. ONT R10 vs. Illumina short reads.

7. Preprocessing

With an overview of the samples and sequencing technologies in place, we now detail our data preprocessing methods, including quality control and assembly strategies.

7.1 Quality control and filtering

For adapter trimming, we used the Porchop_abi (v0.5.0) tool, and for quality control, we used NanoQC. In terms of quality filtering, we tested Chopper (v0.8.0), Filtlong (v0.2.1) and Japsa (v1.9). Chopper showed promising results based on several metrics:

- Number of reads: Number of quality-filtered reads is almost equal to number of raw reads.

- Mean read length remains almost equal to the read length of raw reads.

- Mean quality score: Improved quality score compared to raw reads.

The sequence quality indicated that coverage for ONT reads was lower than that of the short reads. The mean read length of ONT reads was about 11kbp, with a difference of 20kbp in read length between R9 ONT and R10 ONT. The overall mean quality score of the reads was higher for R10ONT (Q14-Q17) compared to R9ONT (Q10-Q12). A negligible number of reads were observed to pass a quality score of Q20 and Q30 in ONTR9 and ONTR10, respectively.

7.2 Assembly

After quality trimming of ONT reads, the reads were assembled using the Flye (v2.9.3) assembler, followed by an initial round of polishing with the Racon (v1.5.0) tool and an additional round of polishing with the Medaka (v1.11.3) tool. Prior to Racon polishing, the reads were mapped to the assembly using the Minimap2 (v2.28) tool. We used two basecalling models for Medaka polishing: r941_min_fast_g303_model.hdf5 (R9ONT) and r1041_e82_400bps_sup_v4.3.0 (R10ONT). Assembly metrics were compared between the assembled contigs of raw ONT (Flye assembly only), polished ONT and short-read technologies using QUAST (v5.2.0) tool and the results are shown in Tables 2-4. The color scheme in the tables represents the respective technologies applied (Illumina – light orange, R9ONT – blue, R10ONT – green).

The average number of contigs in ONT assemblies (1-3 contigs) was lower than that in short-read technology (50-102 contigs), suggesting that the largest assembled contig size (N50) from ONT can encompass the entire genome. The number of base mismatches and misassembled contigs was higher in ONT compared to short-read technology. Additionally, reduced N50 values, exhibiting a difference of 3-fold to 7-fold, were associated with a significant number of misassemblies. Interestingly, assembly metrics were better for microbial species with low GC content compared to those with higher GC content. The number of mismatch bases ranged from approximately 150-300bp in species with low GC content, while in species with high GC content, this figure was around 4000-5000 bp.

Table 2: QUAST assembly metrics for Bacillus anthracis and their respective strains across different sequencing technologies.

| Platform | Sample | Genome fraction (%) | Genomic features | Total aligned length | NGA50 | Misassemblies | Mismatches | # contigs | Largest contig | N50 | GC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | ERR10820686 | 99.09 | 11531 + 58 part | 5456126 | 331382 | 0 | 0 | 47 | 620734 | 331382 | 35.11 |

| ERR10820687 | 99.034 | 11524 + 65 part | 5452575 | 289341 | 0 | 0 | 55 | 1345526 | 289341 | 35.11 | |

| ERR10820690 | 99.033 | 11513 + 65 part | 5452454 | 289138 | 0 | 0 | 59 | 1290244 | 289138 | 35.11 | |

| ONT-R9 | ERR10828761 | 99.894 | 11634 + 12 part | 5503179 | 5233104 | 3 | 249 | 2 | 5233511 | 5233511 | 35.22 |

| ERR10828758 | 99.99 | 11643 + 9 part | 5508241 | 5231265 | 0 | 195 | 3 | 5233940 | 5233940 | 35.22 | |

| ERR10828757 | 99.99 | 11644 + 10 part | 5510323 | 5233390 | 0 | 119 | 3 | 5233821 | 5233821 | 35.21 | |

| ONT-R10 | ERR10828767 | 99.981 | 11644 + 10 part | 5502464 | 5227951 | 2 | 239 | 3 | 5228559 | 5228559 | 35.25 |

| ERR10828764 | 99.984 | 11638 + 16 part | 5504613 | 5227854 | 0 | 204 | 3 | 5230670 | 5230670 | 35.24 | |

| ERR10828763 | 99.984 | 11641 + 13 part | 5511550 | 5228363 | 0 | 123 | 4 | 5229060 | 5229060 | 35.24 |

Table 3: QUAST assembly metrics for Brucella suis strains across different sequencing technologies.

| Platform | Sample | Genome fraction (%) | Genomic features | Total aligned length | NGA50 | Misassemblies | Mismatches | # contigs | Largest contig | N50 | GC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | ERR10820716 | 98.881 | 6558 + 42 part | 3278999 | 170185 | 2 | 4897 | 34 | 531807 | 170339 | 57.21 |

| ERR10820714 | 98.881 | 6556 + 46 part | 3278588 | 155908 | 2 | 4888 | 31 | 531799 | 156009 | 57.24 | |

| ERR10820711 | 98.878 | 6559 + 39 part | 3278434 | 170010 | 2 | 4882 | 31 | 531809 | 184428 | 57.24 | |

| ONT-R9 | ERR10828738 | 99.497 | 6603 + 19 part | 3299711 | 404315 | 16 | 4958 | 2 | 1928723 | 1928723 | 57.21 |

| ERR10828736 | 99.497 | 6603 + 19 part | 3299584 | 404303 | 16 | 4962 | 2 | 1928579 | 1928579 | 57.21 | |

| ERR10828733 | 99.497 | 6601 + 21 part | 3305758 | 450597 | 14 | 4953 | 2 | 2133781 | 2133781 | 57.21 | |

| ONT-R10 | ERR10828744 | 99.126 | 6574 + 32 part | 3305297 | 282065 | 18 | 5149 | 8 | 1400278 | 866836 | 57.21 |

| ERR10828742 | 99.241 | 6592 + 23 part | 3296902 | 404056 | 16 | 5199 | 2 | 1928926 | 1928926 | 57.2 | |

| ERR10828739 | 99.493 | 6600 + 22 part | 3301998 | 450203 | 14 | 5139 | 2 | 2133013 | 2133013 | 57.21 |

Table 4: QUAST assembly metrics for Francisella tularensis strains across different sequencing technologies.

| Platform | Sample | Genome fraction (%) | Genomic features | Total aligned length | NGA50 | Misassemblies | Mismatches | # contigs | Largest contig | N50 | GC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | ERR10820717 | 94.298 | - | 1788588 | 25615 | 0 | 153 | 101 | 88239 | 26988 | 32.17 |

| ERR10820721 | 94.276 | - | 1787414 | 25350 | 1 | 730 | 99 | 88421 | 26987 | 32.17 | |

| ERR10820719 | 94.224 | - | 1787054 | 25623 | 1 | 854 | 102 | 87680 | 26622 | 32.17 | |

| ONT-R9 | ERR10828745 | 99.801 | - | 1893749 | 1890286 | 3 | 213 | 1 | 1895619 | 1895619 | 32.13 |

| ERR10828747 | 99.617 | - | 1888518 | 781455 | 9 | 946 | 1 | 1892668 | 1892668 | 32.14 | |

| ERR10828749 | 99.801 | - | 1890935 | 1658707 | 7 | 881 | 1 | 1895765 | 1895765 | 32.13 | |

| ONT-R10 | ERR10828751 | 99.528 | - | 1886681 | 1566868 | 1 | 208 | 2 | 1571931 | 1571931 | 32.16 |

| ERR10828753 | 97.371 | - | 1849231 | 417031 | 8 | 1083 | 7 | 657510 | 558339 | 32.21 | |

| ERR10828755 | 94.885 | - | 1829187 | 180907 | 4 | 1053 | 17 | 328212 | 289903 | 32.14 |

8. Downstream analysis

Following the preprocessing and assembly steps, we proceed to evaluate the assembled genomes through downstream analyses such as SNP typing, ANI calculation, and phylogenetic inference.

Several downstream analyses were performed for the polished ONT-assembled reads:

- Calculating Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI): ANI was calculated using the fastANI (v1.32) tool. This metric measures the similarity between the assembled genome and the reference genome. Results indicated that the nucleotide identity was 99.8% for all three species across all sequencing technologies.

- Identification of virulence biomarkers: Virulence genes were identified for two species using the Abricate (v1.0.1) tool. Most of the virulent genes were identified for all the technologies with a few exceptions in ONT.

- Plasmid identification: Plasmid identification was performed using the plasmidfinder (kcri-tz/plasmidfinder (github.com)) tool. This analysis focused solely on a single species, and the plasmid was accurately identified in the genome assembly across various technologies.

- Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST): MLST was performed using mlst (v2.23.0). The sequence type was correctly identified for only one of the three species resulting from the R10ONT-assembled genome (with a few exceptions), whereas it was not identified in the R9ONT assembly.

- Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Typing (SNP typing): Identification of SNP using the Snippy (v4.6.0) tool was performed by comparing ONT-based assemblies against the reference genome of the respective species. Similarly, we compared the assembly contigs against the reference genome of the corresponding species for short reads. Following SNP identification, we proceeded with core genome SNP typing for both ONT- and short-read—based assembly contigs.

8.1 Core genome SNP typing

Core genome SNP typing, a standard method to construct phylogenies for closely related microbes, was performed with the Snippy (v4.6.0) tool using standard settings. The pairwise distances of SNPs were calculated using the snp-dists (v0.8.2) tool based on cgSNP alignment, for the reconstruction of phylogenetic trees using Randomized AxeleratedMaximimum Likelihood (RAxML v1.2.2). The resulting phylogenetic trees were visualized with the interactive Tree of Life (iTOL v6.9.1) web tool.

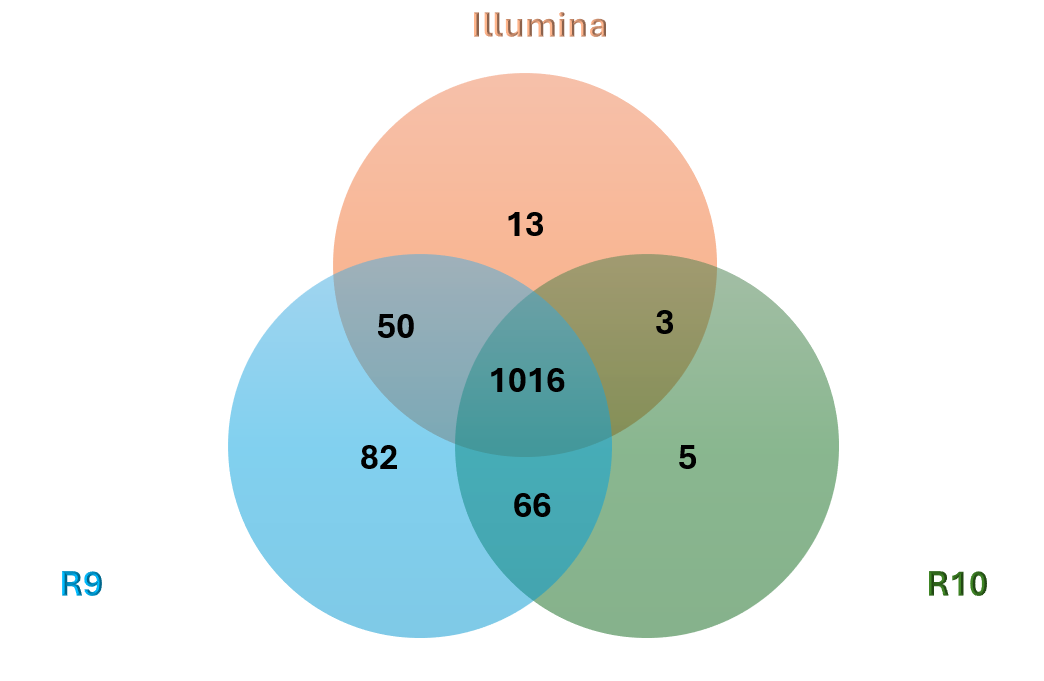

The number of cgSNPs identified by ONT was higher than that of short-read technology for Br. suis, but the number of cgSNPs for R10 ONT was lower than that of short reads for F. tularensis and B. anthracis, indicating possible bias from the reference genome built using short-read technology (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Venn diagrams indicating the SNPs identified across all the technologies for all three species: Francisella tularensis (a), Brucella suis (b), Bacillus anthracis (c).

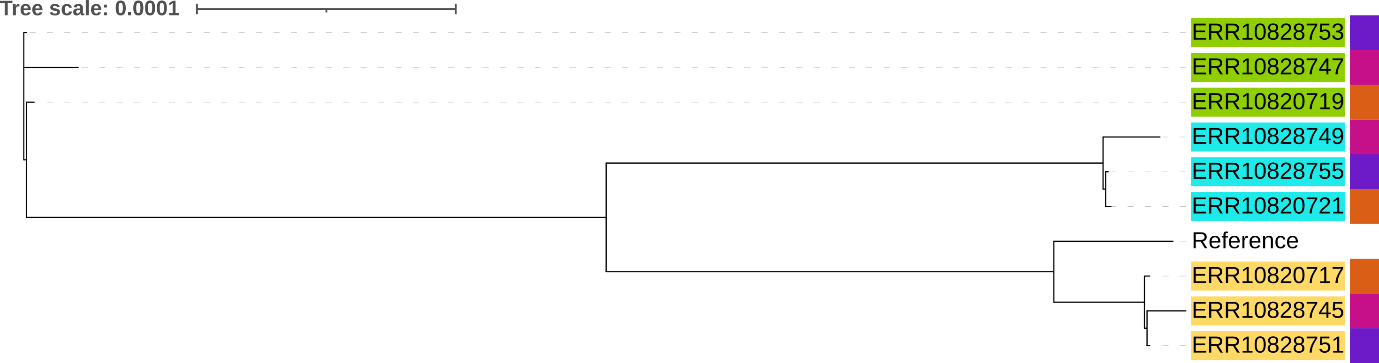

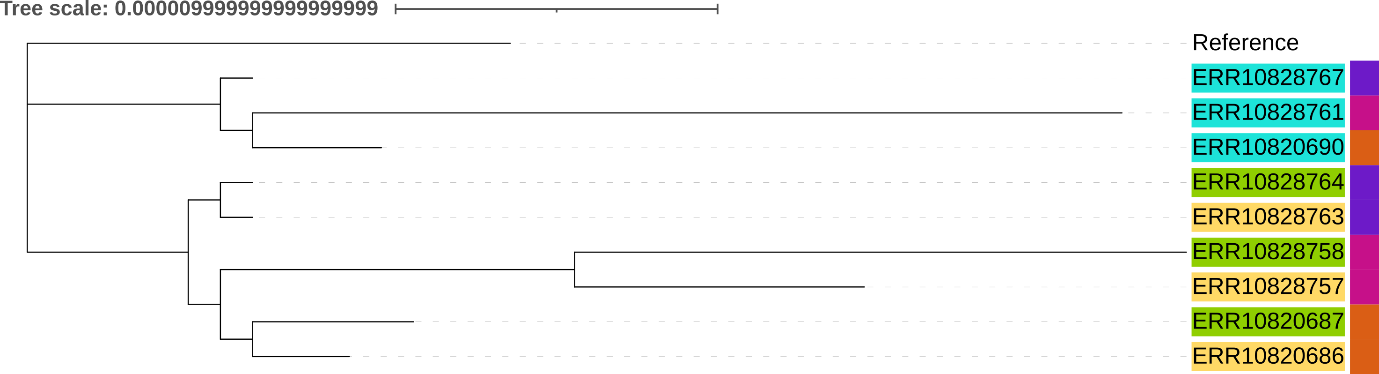

Phylogenetic trees were generated from SNP distance for all three species across various sequencing methods. The number of cgSNPs for R10 ONT was smaller compared to R9 ONT and short reads for F. tularensis (Figure 3). The phylogenetic tree for Br. suis (Figure 4 shows clustering according to strains, independent of the sequencing technology. For B. anthracis, the phylogenies observed were clustered based on outbreak year, independent of the sequencing technology (Figure 5).

Figure 3: Phylogenetic tree constructed for Francisella tularensis from SNP distance for all three strains, comparing assemblies of different technologies and the reference genome. The colors highlighting the run IDs represent different strain IDs (08T0013 – yellow, 10T0192 – green, 15T0012 – blue).

Figure 4: Phylogenetic tree constructed for Brucella suis from SNP distance for all three strains, comparing assemblies of different technologies and the reference genome. The colors highlighting the run IDs represent different strain IDs (08RB2802 – yellow, 08RB3701 – green, 15RB2242 – blue).

Figure 5: Phylogenetic tree constructed for Bacillus anthracis from SNP distance for all three strains, comparing assemblies of different technologies and the reference genome. The colors highlighting the run IDs represent different strain IDs (12RA1944 – yellow, 12RA1945 – green, 14RA5915 – blue).

9. Challenges and limitations

Our findings show that ONT can provide robust phylogenetic clustering, though certain discrepancies remain. In the next section, we discuss the challenges and limitations encountered during our analyses, along with potential improvements.

ONT has shown very promising results for clustering based on phylogenetic trees; however, considering the number of cgSNPs, differences were observed for specific species. The number of cgSNPs observed across technologies was comparable for Francisella tularensis and Bacillus anthracis. However, for Brucella suis, the cgSNPs identified with ONT R10 differed compared to those obtained with short reads and ONT R9. The resulting variation observed between microbial species for the same ONT sequencing technology could be primarily due to certain factors.

One well-known issue is the decrease in ONT accuracy in homopolymer regions. Although errors within homopolymer regions have improved with the ONT R10.4.1 library compared to the ONT R9.4.1 library, very long homopolymers can still cause problems with accuracy. Another possible factor leading to systematic errors within the assembly could be ascribed to DNA modification specific to the microbial species (Forde et al., 2015; Beauchamp et al., 2015). The species-specific modification and motifs not included in the basecaller training set could cause errors with ONT for that specific species. A basecalling model trained and fine-tuned on specific species, including species-specific modified bases in all possible motifs, could be a promising solution to narrow down the observed assembly error for specific species. For example, using a tuned model for Brucella suis could reduce the errors encountered with ONT. Other factors, such as GC content and coverage specific to ONT R10, also cannot be ruled out.

Many ONT-specific tools are released frequently, particularly for assembly methods. In addition to Flye, other assemblers like Canu and Trycycler exist. Canu, though somewhat slower, can produce better assembly than Flye, and both assemblers require minimal manual effort to complete a genome. However, Trycycler has been shown to produce better assemblies than either Canu or Flye, requiring a more complex process involving human judgment and intervention. Exploring other assembly tools beyond Flye could potentially improve the assembly quality for specific species.

In addition, our analysis has some limitations that may influence the observed results. First, we used publicly available FASTQ files generated with the Guppy basecaller, rather than Dorado. Dorado is currently the official Nanopore basecaller and has been shown to be more efficient than Guppy in methylation calling with the 5-hydroxymethylcytosine group (5hmCG) (Dittforth et al., 2023). This newer official basecalling tool could have further improved results for species such as Brucella suis.

Moreover, the tool we used for core genome SNP typing, Snippy, is not specifically optimized for ONT long reads; it relies on Freebayes for SNP calling, whose assumptions may not fully apply to ONT data. We opted for Snippy because no ONT-specific variant caller capable of performing cgSNP analysis was available or optimized for bacterial genomes. Testing ONT-specific tools that do not rely on a reference file—and instead use a pre-trained dataset—could improve results for challenging strains like Brucella suis.

If you would like to know more about any of the topics in this review, please reach out to us at info@zifornd.com.

References:

- Amarasinghe, S. L., Su, S., Dong, X., Zappia, L., Ritchie, M. E., & Gouil, Q. (2020). Opportunities and challenges in long-read sequencing data analysis. Genome Biology, 21(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-1935-5

- Beauchamp, J. M., Leveque, R. M., Dawid, S., & DiRita, V. J. (2017). Methylation-dependent DNA discrimination in natural transformation of Campylobacter jejuni. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(38), E8053-E8061.

- Charalampous, T., Kay, G. L., Richardson, H., Aydin, A., Baldan, R., Jeanes, C., Rao, D., Marque, S., Cordeil, N., Larkin, J., Matuszewski, D. J., Otter, J. A., Parkhill, J., Peacock, S. J., Loose, M., & O'Grady, J. (2019). Nanopore metagenomics enables rapid clinical diagnosis of bacterial lower respiratory infection. Nature Biotechnology, 37(7), 783-792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0156-5

- Dittforth, S., Ozturk, D., & Mueller, M. (2023, May 18). Benchmarking the Oxford Nanopore Technologies basecallers on AWS. Benchmarking Oxford Nanopore basecaller on AWS. November 5, 2024, https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/hpc/benchmarking-the-oxford-nanopore-technologies-basecallers-on-aws/

- Forde BM, Phan M, Gawthorne JA, Ashcroft MM, Stanton-Cook M, Sarkar S, Peters KM, Chan K, Chong TM, Yin W, Upton M, Schembri MA, Beatson SA. 2015. Lineage-Specific Methyltransferases Define the Methylome of the Globally Disseminated Escherichia coli ST131 Clone. mBio 6:10.1128/mbio.01602-15. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.01602-15

- Kolmogorov, M., Yuan, J., Lin, Y., & Pevzner, P. A. (2019). Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nature Biotechnology, 37(5), 540-546. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8

- Koren, S., Walenz, B. P., Berlin, K., Miller, J. R., Bergman, N. H., & Phillippy, A. M. (2017). Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Research, 27(5), 722-736. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.215087.116

- Laver, T., Harrison, J., O'Neill, P. A., Moore, K., Farbos, A., Paszkiewicz, K., & Studholme, D. J. (2015). Assessing the performance of the Oxford Nanopore Technologies MinION. Biomolecular Detection and Quantification, 3, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bdq.2015.02.001

- Linde, J., Brangsch, H., Hölzer, M. et al. Comparison of Illumina and Oxford Nanopore Technology for genome analysis of Francisella tularensis, Bacillus anthracis, and Brucella suis. BMC Genomics 24, 258 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-023-09343-z

- Ni Y, Liu X, Simeneh ZM, Yang M, Li R. Benchmarking of Nanopore R10.4 and R9.4.1 flow cells in single-cell whole-genome amplification and whole-genome shotgun sequencing. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023 Mar 24;21:2352-2364. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2023.03.038. PMID: 37025654; PMCID: PMC10070092.

- Nurk, S., Walenz, B. P., Rhie, A., Vollger, M. R., Logsdon, G. A., Grothe, R., Miga, K. H., Eichler, E. E., Phillippy, A. M., & Koren, S. (2022). HiCanu: accurate assembly of segmental duplications, satellites, and allelic variants from high-fidelity long reads. Genome Research, 32(9), 1917-1932. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.275658.121

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies. (2023). Nanopore-Only Microbial Isolate Sequencing Solution.

- Sedlazeck, F. J., Rescheneder, P., Smolka, M., Fang, H., Nattestad, M., von Haeseler, A., & Schatz, M. C. (2018). Accurate detection of complex structural variations using single-molecule sequencing. Nature Methods, 15(6), 461-468. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-018-0001-7

- Sereika, M., Kirkpatrick, J. M., Bobonis, J., Depta, G. B., Leidel, S. A., & Butter, F. (2022). Oxford Nanopore R10.4 long-read sequencing enables near-perfect de novo assemblies of a diploid yeast genome. Molecular Systems Biology, 18(7), e11159. https://doi.org/10.15252/msb.202211159

- Tange, O., Blythe, A. J., & Swift, J. (2021). Nanopore sequencing of RNA and DNA from marine organisms. Marine Genomics, 57, 100825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margen.2020.100825

- Tyler, A. D., Mataseje, L., Urfano, C. J., Schmidt, L., Antonation, K. S., Mulvey, M. R., & Corbett, C. R. (2018). Evaluation of Oxford Nanopore's MinION Sequencing Device for Microbial Whole Genome Sequencing Applications. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 10931. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29334-5

- Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M., Gorrie, C. L., & Holt, K. E. (2017). Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLOS Computational Biology, 13(6), e1005595. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595